This is the mobile-friendly web version of the original article.

“Draw the Internet.” A visual exploration of how children think an everyday technology.

University of Rhode Island

DigitalCommons@URI

Journal of Media Literacy Education Pre-Prints

June 2021

Luca Botturi

Major: B.S. Computer Science

Scuola universitaria professionale della Svizzera italiana, Switzerland, [email protected] Laboratorio tecnologie e media in educazione Dipartimento formazione e apprendimento Scuola universitaria professionale della Svizzera italiana [Email] luca.botturi ‘at’ supsi.ch

Video: Why The University of Rhode Island?

Recommended Citation Botturi, L. (2021). “Draw the Internet”: A visual exploration of how children think an everyday technology. Journal of Media Literacy Education Pre-Prints. Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/jmle- preprints/7

This Research Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@URI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Media Literacy Education Pre-Prints by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@URI. For more information, please contact [email protected].

- Introduction: An invisible everyday medium

- Why understanding the Internet matters

- How children understand the Internet

- Results

- Discussion

- References

Abstract. The Internet is today a significant part of children’s daily lives, and digital competences have been included as basic learning goals in many school systems worldwide. In order to develop sound and effective early-age Internet education programs, information about how children use the Internet should be integrated with insights in how they understand it. This study investigates 8-to-10- year-old children’s understanding of the Internet through the qualitative analysis of 51 drawings collected in three primary school classes in Switzerland. The results confirm that children’s conceptions of the Internet are rich but often inaccurate or uncomplete. The conceptions collected in this study partially differ from those emerged in previous studies, possibly due to the diffusion of smartphones and tablets and to the commercialization of the Internet. Also, each class presents a different balance of conception types, resulting in a sot of class understanding of the Internet.

Keywords. Internet education, primary school, drawings, digital literacy, conceptualization.

Introduction: An invisible everyday medium

The Internet is today a given-for-granted commodity. In large areas of the world, and especially in Western countries, access to the Internet is over 90% (ITU, n.d.) so that actions like “look it up on Google” or “check the weather online” have become commonplace, like turning on a toaster or opening the hot water tub.

The Internet is also part of the everyday life of children, as smartphones and tablets are always at hand, providing anywhere/anytime access; on average European children spend almost 3 hours per day online (Smahel et al., 2020). If we add in smart TVs and other web appliances like smart bands or videogame consoles we can conclude that the Internet is “one of the meaningful life-worlds of 21st century children” (Mertala, 2019, p.56). This is also true in Switzerland, the country where the present study is located, and where 96% of children aged 6 to 12 report the presence of many connected devices in their homes, and about 60% are online at least one time per week (Genner et al., 2017).

The Internet is a technological global and decentralized infrastructure that supports a huge number of different services. As some of the pioneers in Internet development put it, it can be described as “at once a broadcasting capability, a mechanism for information dissemination, and a medium for collaboration and interaction between individuals and their computers without regard for their geographic location” (Leiner et al., 2009, p.22). In its essence, it can be described as a technological network, made of computers and cables, that is operated thanks to open protocols such as TCP/IP or HTTP.

But the Internet is not just a technology: the breadth and width of its use make it a diffused socio-technical system (Whitworth, 2011), that we can describe as a media-rich environment, which entails complex and global commercial activities that also have an impact on Internet-based services and on how we use them (Srnicek, 2017). The social dimension of the Internet emerged originally from the pioneers of the web, who intended it rather idealistically as “a world that all may enter without privilege or prejudice accorded by race, economic power, military force, or station of birth (…) where anyone, anywhere may express his or her beliefs, no matter how singular, without fear of being coerced into silence or conformity” (Barlow, 1996). From a research point of view, the Internet is a social environment, a cultural tool kit and a new object of cognition (Greenfield & Yan, 2006).

Understanding the Internet is a challenge not only for the young ones, but also for adults. Indeed, the Internet is relatively new technology, it is virtual (i.e., it is not visible or directly measurable), it is connective and open in nature, and this makes it difficult to understand (Yan, 2006). Moreover, the pervasiveness of the Internet is also due to the fluidity of the user experience, which use it smoothly and in most cases effortlessly (Lin, 2008) – and we tend not to notice technologies that simply work and require no fixing.

This study investigates 8-to-10-year-old children’s understanding of the Internet through the qualitative analysis of 51 drawings collected in three primary school classes in Switzerland. In the next section, I will briefly discuss the relevance of research aimed to generate insights in how children understand the Internet, while the third section will provide a summary of the current research on the topic. In the following sections I will illustrate the methodology and the results of the study, that will be followed by the discussion.

Why understanding the Internet matters

When teachers teach children about butterflies, they first inquire about their spontaneous views: where they think that butterflies come from, how they are born, if there are different types, etc. For good teachers, this is the starting point for integrating new knowledge and developing new competences. In a similar way, understanding children’s digital practices and experiences is a requirement in order to develop effective Internet education and promote digital skills: while young people do not have a technically accurate understanding of the Internet, they possess a maybe naïve but not trivial experience (Murray & Buchanan, 2018), that educators cannot just ignore and start as if “from scratch”.

Up to now, most research is about how often and in what way children and young people use the Internet, but not on how they understand it (Anderson et al., 2017). Understanding practices, i.e., how children use the Internet (e.g., with what devices, for how long and to do what) is paramount, because playing online videogames is different than doing research for homework or texting with friends, and time and balance of on- and off-screen activities matter. But this is only half of the picture: in order to design effective Internet education, teachers, parents and educators need to understand how children think the Internet, i.e., how they conceptualize the technology they use. Such research is important for at least five reasons.

First, a sound conceptualization of the Internet is a key element in any digital competences or digital citizenship model such as DigComp 2.1 (Carretero et al., 2017) or (JISC, 2014): skimming through the titles of the model’s dimensions is enough to realize that the Internet is basically everywhere, like a frame within which all definitions acquire meaning. For example, both reading and learning online involve specific epistemic beliefs about the Internet (Strømsø & Kammerer, 2016), which are then reflected in the Information and data literacy competence domain.

Second, recent research indicates that in order to cope with the massive and fastpaced digitalization of society, citizens need to develop computational thinking skills, i.e. an approach to solving problems, designing systems and understanding human behaviour that draws on concepts fundamental to computing (Wing, 2006). How we conceptualize the Internet and digital connectivity is a component in the development of computational thinking (Wing, 2008).

Third, today’s digital and media literacy competence models often integrate the legacy of the media education tradition, whose first formalization can be found in Len Masterman’s seminal work Teaching the media (2003). A key element in his media education paradigm is the critical understanding of the “production systems” of each media, which include both technical and social specifications. The Internet is one of the key elements in today’s media production systems: its configuration influences the languages, formats and genres, and determines the instruments that authors and production houses use to control their messages and feedback. Such a view perfectly fits within the current multiple literacies paradigm (The New London Group, 1996).

Fourth, effectively addressing the concerns of parents and institutions about children’s online safety requires adults and educators to get an idea of how children understand the Internet: “it is not possible to teach children about cyber-safety until more is known about how they understand the Internet in the first instance” (Edwards et al., 2015, p. 46).

Finally, exploring children’s conceptualization of the Internet is also a matter of equity, as gaps in understanding the Internet begin quite early (Dodge et al., 2011), and might jeopardize later attempts to develop sound digital skills.

How children understand the Internet

Developing a mature Internet concept

Understanding the Internet can be framed as the development of the mental model or concept of an artefact (Keil, 1989) as opposed to natural, social and mental concepts (Carey, 1985). Recent studies in this area (Edwards et al., 2015; Yan, 2005) use Vygotsky’s theory of conceptual development (Vygotsky, 1987). According to such theory, “before children reach a mature concept of, say,* triangle* they go through a whole series of pre-conceptual stages during which they may use the word triangle, but have in mind something that is quite different from the adult concept” (van der Veer, 1994, p. 295). Vygotsky calls such pre-scientific concepts everyday concepts, i.e., conceptualizations that emerge only from direct experiences and practices. Through education, such concepts gradually evolve into scientific concepts, that supposedly explain reality more accurately and form part of interconnected notions.

At different stages of a child’s development, the meaning of “Internet” will therefore change, “much like chess pieces acquire different meaning as the player becomes more experienced” (van der Veer, 1994, p. 296). This means that children live in the same physical environment (Umwelt) as we do, but at the same time experience a different semantic world (Welt). Education can be understood as creating a bridge between these two worlds, and between generations, i.e., between adult’s and children’s meaning-worlds. In order to explain complex experiences and objects, children of early age might for example develop animistic or magic thinking (Lévi-Strauss, 1962), and this is indeed reflected in some recent studies, which identify an animistic understanding of computers (Mertala, 2019), e.g., attributing “intelligence” or “will” to computers. Such a concept will gradually evolve through experience (e.g., understanding how the computer works, and that it reacts as a machine to specific commands), and might be integrated with scientific concepts (e.g., that a computer is a programmable machine, and that coding is the activity to program it).

The importance of mature concepts is not only cognitive, as “the influence of mature conceptual thinking (…) is not confined to the cognitive domain but will at the same time lead to more mature aesthetic reactions and a more refined emotional life” (van der Veer, 1994, p. 297) – a paramount remark for the development of effective Internet safety education, which is tightly connected to emotions and to aesthetic and ethic behaviours.

This study follows this path, trying to capture the everyday concepts of the Internet of children who had little or no prior explicit instruction on the topic.

The technical and the social Internet

Research on how children aged 3 to 10 conceptualize the Internet so far is sparse, and mostly report that children are unfamiliar with the Internet concepts (Edwards et al., 2018): they can use online services and applications, but cannot explain how they work. Sideways, this provides interesting insights into the definition of the digital competences of so-called “digital natives”. For example, Eskelä-Haapanen & Kiili (2019) found that 33% of the children they interviewed were simply “unable to describe” the Internet, although they used it rather often. Interestingly, while children’s conceptions of the Internet are minimal (Murray & Buchanan, 2018; Yan, 2005), it also appears that adults’ conceptions are not much more accurate (Yan, 2005).

Most studies (Dodge et al., 2011; Eskelä-Haapanen & Kiili, 2019; Mertala, 2019; Yan, 2006) describe and analyse children’s conception of the Internet as spanning from technical or tool-based (e.g., “it has to do with electricity”) to social or related to social practices (e.g., describing situations in which they use the Internet or potential threats to online safety). This reflects the definition of the Internet as a socio-technical system, and also the recent developments of digital and media literacy research, which distinguish digital “functionings” from the actual application of digital competences in specific situations (McDougall et al., 2018). Many children, when asked to visualize the Internet draw a device such a computer or a smartphone, or interpret it as a place (Murray & Buchanan, 2018). The conceptualization span from technical to social also emerged in this study; however, other categories also intervened, supporting the formulation of a more nuanced view.

In general, very young children “did not conceptualize the Internet outside of specific uses” (Dodge et al., 2011, p. 93). Children’s conceptualizations seem to be related to particular contexts, namely family, information, and entertainment (Edwards et al., 2018) – but interestingly not to school, communication, media production, or just informatics or technology as such. This seems to confirm the nature of everyday concepts of their conceptualizations.

It must be noted however, that end-user Internet technologies change at an incredibly fast pace, and so do the related social practices. For example, over the last five years we witnessed the appearance and diffusion of Snapchat, Fortnite, Netflix and Disney+; each of them changed children’s digital media landscape and made previous research partially obsolete. A constant focus on the evolution of the digital landscape is paramount to transform research results into educationally useful insights and guidelines.

Influences on the conceptualization of the Internet

Some studies also investigated the factors that contribute to the development of children’s conceptualizations of the Internet. Yan’s studies (2005; 2006), although not recent, provide the most interesting insights. Yan concludes that there are no effects of duration of Internet use on children’s understanding of the technical and social complexity of the Internet; on the other hand, frequency of use and informal internet classes have a slight positive effect. However, “direct online experience alone is unlikely to determine completely cognitive and social understanding of the Internet” (Yan, 2005, p. 394).

Also, older children (over 10 years) have a greater technical and social understanding of the Internet than younger children, which could be explained with the achievement of Piaget’s formal operational stage of cognitive development, in which abstract thinking with no need of direct manipulation becomes an effective mode of learning (Inhelder & Piaget, 1958). Gender does not seem to play a significant role (Yan, 2006).

It is interesting to notice that children’s understanding of the technical nature of the Internet seems to advance their understanding of its social complexity, but no vice versa (Yan, 2006). This makes sense because, as mentioned earlier, “the Internet is first and foremost a technological system, like a car or an airplane, rather than a social system, like a school or a village” (p. 426).

Method

Collecting evidence of children’s conceptualization is not easy. Previous studies used interviews (Dodge et al., 2011; Edwards et al., 2015; Eskelä-Haapanen & Kiili, 2019) or focus groups (Murray & Buchanan, 2018), or a combination of interviews and drawings (Mertala, 2019). In some cases, children were asked to draw directly on the survey form (Yan, 2006).

This study tried to collect evidence about everyday conceptualizations blending in the regular school work, and for this reason decided to refrain from any interview, lab or other experimental setting unfamiliar to children. This was also important in order to reduce the risk of the priming effect (Bargh & Chartrand, 2014). During school year 20219/20 I was engaged in three class projects on digital skills. All projects represented the first step of explicit Internet education for each class, and all started with a special full-day session on how the Internet works. As a preparation to that moment, one week in advance, the teachers asked their pupils to “draw the Internet, as you see it”. This is indeed a common pre-conception collection strategy of those teachers in their schools, using a common expressive mode such as drawing. Teachers set the technique (A4 paper and pencils) and set the time (45’ to 50’) but provided no further guidance or advice on what or how to draw.

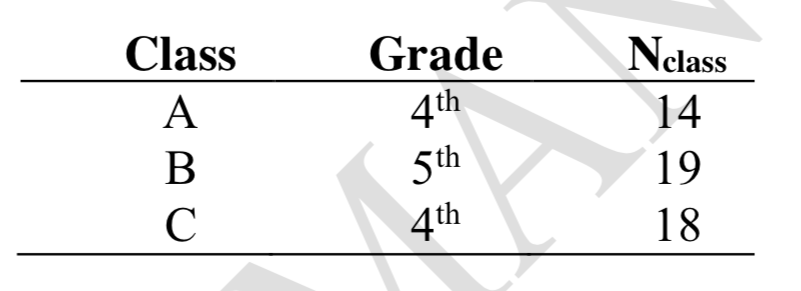

Overall, through such a convenience sample, I collected 51 finished drawings of children in grades 4 (N=31, age 9-10) and 5 (N=20, age 10-11), of age between 9 and 11 (see details in Table 1). Some of the drawings are very similar to each other (e.g., they represent app icons), so that it was easy to group them by subject. When I met each class, we took time to review together at least one drawing per group: we discussed it in order to generate a shared understanding of what the drawing represented. Such discussions were considered during the following coding phase in order to solve any ambiguities in interpretation.

Table 1. Sample characteristics (Ntotal=51).

The document analysis process (Bowen, 2009) was designed in order to focus on children’s experiences (Edwards et al., 2018) and not to classify their drawings as right / wrong, or to assess them against a rubric. The drawings were considered as a valuable source of information about how young ones understand their world (Mertala, 2019), and consequently as an effective entry-point for educational or training activities.

The drawings were first analysed by the author, who identified a set of tags that described the drawings both as content and form. Tags were progressively refined by saturation, i.e., as along a no additional tag seemed necessary to represent salient drawing features. A first set of 7 randomly chosen drawings were then independently tagged by another coder, who was asked to start from the same set of tags but was given the possibility to change, eliminate or insert tags. Inter-rater reliability at this stage was .83, which is good. After a joint review and discussion of this first set, the definitive set of tags was defined, and a second set of 7 drawings were independently coded by the two coders. Inter-rater reliability at this stage was .92, which is very good. Differences in coding were resolved through discussion. The two reviewers then re-coded together the remaining 37 drawings.

The final set of tags is presented in Table 2, where they are grouped in two categories:

Main subject tags are 6 tags that describe what is represented in the drawing, its main subject. For example, “apps” will be used in the case the drawing depicts app icons in the foreground, but not in the case of a drawing representing a daily situation in which a detail is an icon on a screen.

Formal tags are two tags that capture formal features of the drawing, namely the use of colours and the self-representation of the author in the drawing.

Tags are cumulative and mutually non-exclusive, i.e., every single drawing can have one or more tags. For example, drawing A14 presented in Figure 1 is tagged as A14[devices, situation; colour, myself]; on the other hand, C4 presented in Figure 2 is tagged as C4[devices, apps; colour].

Table 2. Classification tags.

Some drawings very clearly expressed also a value judgment about the Internet, indicating that it was positive (e.g., useful or interesting) or negative (e.g., harmful or stupid). 7 drawings where therefore tagged with “positive/negative” according to that. One example is drawing B8, which is illustrated in Figure 3 and is tagged as B8[myth, app, situation; myself; negative]; the comic balloons say: “Dinner is ready!” “No, I’ll eat here!”.

![Figure 1. A14[devices, situation; colour, myself]](https://statics.bsafes.com/images/papers/draw-the-internet-a-visual-exploration-of-how-children-think-an-everyday-technology-fig-1.png) Figure 1. A14[devices, situation; colour, myself].

Figure 1. A14[devices, situation; colour, myself].

![Figure 2. C4[devices, apps; colour].](https://statics.bsafes.com/images/papers/draw-the-internet-a-visual-exploration-of-how-children-think-an-everyday-technology-fig-2.png) Figure 2. C4[devices, apps; colour].

Figure 2. C4[devices, apps; colour].

![Figure 3. B8[myth, app, situation; myself; negative].](https://statics.bsafes.com/images/papers/draw-the-internet-a-visual-exploration-of-how-children-think-an-everyday-technology-fig-3.png) Figure 3. B8[myth, app, situation; myself; negative].

Figure 3. B8[myth, app, situation; myself; negative].

Results

As a consequence of the “natural” school setting and of the time devoted to it, the collected drawings are mostly highly elaborated and go well beyond a sketch to illustrate an idea; they are actually more that kind of drawing that children would include in their personal folder and show their parents as part of the work done at school. In fact, most of them are rich and coloured representations, so that we can assume that they represent something more than “the first thing that comes into mind” when thinking about the Internet.

Drawing’s subjects

The frequencies of subjects represented in the drawings are displayed in Figure 4. The largest part of children (n=32) represented app icons or screens, as in the sample drawing in Figure 5. This is indeed an interesting result as it was not reported in any of the previously mentioned studies: the Internet today seems to be better represented using app brands and icons, instead of computers and devices. On the other hand, drawings representing the content of web pages (e.g., items on shopping sites, or touristic information) are only a smaller proportion (n=5).

It is interesting to notice that icons are usually very precisely replicated, including using the right colours, while the names of even very common apps (like WhatsApp or YouTube or Google) are often misspelled.

Figure 4. Subjects frequencies (N=51).

Figure 4. Subjects frequencies (N=51).

Figure 5. A drawing representing app icons (B17).

Figure 5. A drawing representing app icons (B17).

However, still many drawings (n=16) represent devices, as the one in Figure 2 above; they are usually wireless personal devices such as smartphones or tablets, and more rarely computers. Such finding confirms that the Internet is often conceptualized as something which is “in” the computer, or as something that is visible via a device – just like in other studies the monitor was used to represent the whole computer (Mertala, 2019).

Several drawings depict the Internet as accessible from more than one device, and from devices of different types that can be connected together, as illustrated in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Internet as connecting more devices of different types (A3).

Figure 6. Internet as connecting more devices of different types (A3).

Interestingly and differently from previous studies, only few drawings (n=6) represent situations in which characters actually. use the Internet. Such situations are usually related to family and communication with friends, or depict conflictual situations, like somebody getting a smaller brain because he uses the Internet too much or a discussion with the parents as in the drawing in Figure 3 above. The few drawings (n=9) in which the author included him- or herself in the picture mostly fall in this category, even if a few children represented themselves in metaphorical/mythical representations.

Myths and metaphors

Of all the tags emerged during the classification, one captures a category that was not used in any of the reviewed studies: “myth”. This tag was used to classify 17 drawings, i.e. about one third of the sample, a proportion comparable to the “devices” tag.

This category includes drawings that in some way try to describe or explain the Internet using metaphors or other more or less fantastic representations. Most of the drawings represent the Internet as a place neatly organized in silos or blocks or skyscrapers, like a sort of densely populated down-town area (Figure 7). The elements in such representations are usually associated with apps like YouTube or Google or Messenger, or with school subjects or other topics like Geography, Nature, Stories, etc.

Figure 7. The Internet as a city (A2).

Figure 7. The Internet as a city (A2).

Other mythical representations are more fantastic, and represent the Internet as a sort of sci-fi fairy tale in which strange and fancy elements create a new world, as in Figure 8, where we can see “mouse arrows, both male and female” (as the young author of the drawing nicely put it during the discussion) in a sort of control room. Another interpretation is about something that envelops the whole globe and transforms it (Figure 9).

Figure 8. The Internet as a fantastic space (A4).

Figure 8. The Internet as a fantastic space (A4).

Representing the network

A few children (n=9) represented the Internet as a network. Even though the figure is rather small, this conceptualization of the Internet is closer to its actual technical nature and is therefore interesting to analyse how such networks are represented.

A few network drawings just represent an apparently unordered mesh of traits or links, with no nodes, like a sort of messed-up spider web, with no recognizable centre, periphery or shape. Other drawings integrate some connective elements and technology parts into links that directly connect websites or apps to end-user devices (Figure 10). This could be described as a shallow network, as it consists basically in links that connect the visible parts of the system (websites, apps, devices) among them and to users, with no central or hidden element or logic.

Figure 9. The Internet enveloping the world (A10).

Figure 9. The Internet enveloping the world (A10).

Figure 10. A “shallow network” representation (A12)

Figure 10. A “shallow network” representation (A12)

Another group of network visualizations is more technically accurate, and represents a network of computers or technological nodes and links, that in some cases goes all around the world. While this is not the case with the real Internet, most connections in such representations are wireless, and satellites are always present. This is possibly due to the technical fluidity (Lin, 2008) commented above, and corresponds to what was also found in (Mertala, 2019).

Class matters

While the sample size is too small to support any segmentation or statistical analysis, one last interesting exploration of the drawings comes from frequencies by class, as subjects appear to be rather unevenly distributed, as illustrated in Figure 11 (frequencies have been transformed in percentages in order to eliminate the effect of class size).

Figure 11. Subjects frequencies by class (normalized)

Figure 11. Subjects frequencies by class (normalized)

For example, 64% of the drawings in class A represent a myth or metaphor, indicating that this is possibly a group with powerful imagination, open to stories and narrations. In class B we have a rather high share of drawings representing a network (26%, against 14% and 11% in the two other classes); this means that at least one fourth of the pupils have an idea that Internet is a technological interconnected system. In class C, on the other hand, we have a very high number of device drawings. Such observations provide useful indications for starting an Internet education program in each class, and adapting it to the specific situation. From a practical point of view, just like each class hosts a different range of Internet practices (Botturi, 2019b), it can be expected that it also has a different constellation of everyday Internet concepts, a sort of “class understanding of the Internet”, so that even ready-made activities could (and should) be adapted for improved effectiveness. In this sense, colleting drawings from a class can be a useful way to “listen” to its pupils and take they experience into account.

Discussion

The study presented in this paper is about 8- to 10-year-old Swiss children’s everyday conception of the Internet, investigated through the analysis of 51 drawings collected from 3 primary school classes. Their analysis provided a confirmation of the main results of previous studies along with new insights.

The drawings were not tagged as correct or wrong, but were analysed as rich sources of information, with the intent to capture the richness of the presented conception of the Internet. Nonetheless, from both a technical and social point of view, such conceptions are often inaccurate or uncomplete, confirming the outcomes of previous studies (Mertala, 2019). While it is something they regularly use, the Internet’s workings remain a mystery even for these “digital natives”, who do not seem to have any special insights into digital technologies – also confirming previous research (Zampieri et al., 2018). The tension between a “daily” instrument and the perception of its complexity is well documented in a category of drawings which did not appear in previous research, namely, the representation of myths and metaphors. Such visualization can be interpreted as the activation of magic thinking in order to tackle with complexity, and they clearly indicate that children wonder about the technologies they use and are eager to learn about them.

The appearance of a majority of drawings representing app icons and smartphone screens, which had also never been discussed in previous studies, might be a hint of the ongoing evolution of the conceptualization of the Internet in relation to that of the Internet as such. The focus on app logos rather than on devices clearly depends on the extreme penetration of smartphones as primary personal connectivity devices, and can indeed be interpreted as an effect of the commercialization of the Internet (Press, 1994), whose use is more and more mediated by commercial services. Perceiving the Internet primarily as place only accessible through a layer of commercial applications is indeed a major turn, actually moving users further away from its technical understanding towards a rather specific facet of its social nature. On the one hand, if we consider the relationship between the technical and social understanding of the Internet that was illustrated above (Yan, 2006), we might infer that such a commercial turn will at the same time make the Internet more opaque, and Internet education more difficult; on the other hand, such a perception in young children marks a distance from the pioneers’ conception of the network as a space of freedom, self-expression and creativity (Barlow, 1996).

If education to the Internet – both to its understanding and to its safe, legal, critical and creative use – is a priority, so is the exploration of children’s conceptions of the network, as they are the basis on which any learning program can be designed, carried out and assessed. While we observe and research the digital generation gap, educators should find ways to listen and consider their students’ digital experiences and understandings.

This study provides initial evidence that Internet conceptions evolve in time as the technology does, from one generation to the next; previous studies (Yan, 2005) also indicate that individual conceptions also develop with age, experience and learning. The exploration of how children think the Internet and digital technologies in general should become an ongoing and coordinate effort, integrating the more developed landscape of teens and young people Internet use research. It is not just a matter of preventing risks, but also of learning to see the digitalization with the eyes of the next generation.

The collection of robust evidence in this domain would also indicate viable paths for Internet education, e.g., developing knowledge and skills starting from how children actually see it: as a place for having fun, as a place with lots of contents, as a place for doing research and learning, etc. From an educational point of view, the technology fluidity discussed above (Lin, 2008) seem to represent a central point: the Internet seldom becomes an object of reflection because it can be simply given for granted. Engaging in problem solving, also including malfunctioning technologies (Mertala, 2019), could possibly be an effective educational approach.

The research method of this study emphasized the ecology in data collection, focusing solely on drawings. While this provided extremely rich original documents, it also prevented data triangulation. Further research in this direction could consider the combination of drawing analysis with qualitative data such as interviews or focus groups, or with socio-demographic data.

An interesting path of research would explore the elements that contribute to the development of a specific conception of the Internet. Previous studies report intentional or unintentional tutoring from parents and siblings (Mertala, 2019), but the role of schools and formal education could and should be further explored. The examination of the quality of classroom discussions about the Internet (EskeläHaapanen & Kiili, 2019) would provide a favourable observation point, that could positively integrate the analysis of children’s productions. The exploration of children’s understanding of other everyday technologies – from smartphones to digital assistants, from robots to ATM, or also of non-digital machines – would equally generate interesting insights. The comparison of conceptions of the Internet across different age group would also yield interesting insights in a quasilongitudinal study; in the same way, the comparison of different social groups (e.g., urban vs. rural) or of groups from different countries or cultural backgrounds would equally be of interest.

Finally, a key element in the Internet education landscape is teachers’ and educators’ conceptions of the Internet: they confidence in what they know about what they have to teach, along with the availability of sound teaching and learning instruments (Botturi, 2019a), is the cornerstone of any Internet education program (Instefjord, 2015; Lund et al., 2014).

References

Anderson, E. L., Steen, E., & Stavropoulos, V. (2017). Internet use and Problematic Internet Use: A systematic review of longitudinal research trends in adolescence and emergent adulthood. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 22(4), 430–454. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2016.1227716

Bargh, J. A., & Chartrand, T. L. (2014). The mind in the middle: A practical guide to priming and automaticity research. In H. Reiss & C. Judd, *Research methods in social psychology, *New York:Cambridge University Press, pp. 1-61.

Barlow, J. P. (1996). A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace. Available at https://www.eff.org/cyberspace-independence

Botturi, L. (2019a). Digital and media literacy in pre-service teacher education. Nordic Journal of Digital Literacy, 14(03–04), 147–163. Doi: https://doi.org/10.18261/issn.1891-943x-2019-03-04-05

Botturi, L. (2019b). When the big picture is not enough. Media Education Research Journal, 9(1), 12–33.

Bowen, G. A. (2009). Document analysis as a qualitative research method. Qualitative Research Journal, 9(22), 27–40. Doi: https://doi.org/10.3316/qrj0902027

Carey, S. (1985). Conceptual Change in Childhood. Cambridge University Press.

Carretero, S., Vuorikari, R., & Punie, Y. (2017). The Digital Competence Framework for Citizens. Publications Office of the European Union. Doi: https://doi.org/10.2760/38842

Dodge, A. N., Nahid Husain, & Nell K. Duke. (2011). Connected Kids? K-2 Children’s Use and Understanding of the Internet. Language Arts, 89(2), 87–98.

Edwards, S., Nolan, A., Henderson, M., Mantilla, A., Plowman, L., & Skouteris, H. (2018). Young children’s everyday concepts of the internet: A platform for cyber-safety education in the early years: Young children’s everyday concepts about the internet. British Journal of Educational Technology, 49(1), 45–55. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12529

Edwards, S., Skouteris, H., Nolan, A., & Henderson, M. (2015). Young children’s internet cognition. In Understanding Digital Technologies and Young Children (pp. 38–45). Routledge.

Eskelä-Haapanen, S., & Kiili, C. (2019). ‘It Goes Around the World’ – Children’s Understanding of the Internet. Nordic Journal of Digital Literacy, 14(03–04), 175–187. Doi: https://doi.org/10.18261/issn.1891-943x-2019-03-04-07

Genner, S., Suter, L., Waller, G., Schoch, P., Süss, D., & Willemsee, I. (2017). MIKE - Medien, Interaktion, Kinder, Eltern. Ergebnisbericht zur MIKE-Studie 2017. Zürcher Hochschule für Angewandte Wissenschaften.

Greenfield, P., & Yan, Z. (2006). Children, adolescents, and the Internet: A new field of inquiry in developmental psychology. Developmental Psychology, 42(3), 391–394. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.42.3.391

Inhelder, B., & Piaget, J. (1958). The growth of logical thinking from childhood to adolescence: An essay on the construction of formal operational structures (Vol. 22). Psychology Press.

Instefjord, E. (2015). Appropriation of digital competence in teacher education. Nordic Journal of Digital Literacy, 10 (Jubileumsnummer), 155–171.

ITU. (n.d.).* ITU Statistics*. Available at https://www.itu.int/en/ITUD/Statistics/Pages/stat/default.aspx

JISC. (2014). Developing digital literacies. Available at https://www.jisc.ac.uk/guides/developingdigital-literacies

Keil, F. C. (1989). Concepts, kinds, and cognitive development. Cambridge University Press.

Leiner, B. M., Cerf, V. G., Clark, D. D., Kahn, R. E., Kleinrock, Lynch, D. C., Postel, J., Roberts, L. G., & Wolff, S. (2009). A brief History of the Internet. ACM SIGCOMM Computer Communication Review, 39(5), 22–31.

Lévi-Strauss, C. (1962). La pensée sauvage (Vol. 289). Plon Paris.

Lin, C. A. (2008). Technology fluidity and on-demand webcasting adoption. Telematics and Informatics, 25(2), 84–98. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2006.06.002

Lund, A., Furberg, A., Bakken, J., & Engelien, K. L. (2014). What does professional digital competence mean in teacher education? Nordic Journal of Digital Literacy, 9(04), 280–298.

Masterman, L. (2003). Teaching the media. Routledge.

McDougall, J., Readman, M., & Wilkinson, P. (2018). The uses of (digital) literacy. Learning, Media and Technology, 43(3), 263–279. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2018.1462206

Mertala, P. (2019). Young children’s conceptions of computers, code, and the Internet. International Journal of Child-Computer Interaction, 19, 56–66. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcci.2018.11.003

Murray, T., & Buchanan, R. (2018). ‘The Internet is All Around Us’: How Children Come to Understand the Internet. Digital Culture & Education, 10(1), 1–21.

Press, L. (1994). Commercialization of the Internet. Communications of the ACM, 37(11), 17–21.

Smahel, D., MacHackova, H., Mascheroni, G., Dedkova, L., Staksrud, E., Olafsson, K., Livingstone, S., & Hasebrink, U. (2020). EU Kids Online 2020: Survey results from 19 countries. Doi: https://doi.org/10.21953/lse.47fdeqj01ofo

Srnicek, N. (2017). Platform capitalism. John Wiley & Sons.

Strømsø, H. I., & Kammerer, Y. (2016). Epistemic cognition and reading for understanding in the internet age. In J. A. Greene, W. A. Sandoval, I. Bråten, Handbook of Epistemic Cognition, Routledge, pp. 230–246.

The New London Group. (1996). A pedagogy of multiliteracies: Designing social futures. Harvard Educational Review, 66(1), 60–93. Doi: https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.66.1.17370n67v22j160u

van der Veer, R. (1994). The concept of development and the development of concepts. Education and development in Vygotsky’s thinking. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 9(4), 293–300. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03172902